A Night with a Maya Family: What Really Happens in Guatemala's Highland Homestays

Forget tourist gers and temple lodges. In Guatemala's Maya villages around Lake Atitlán, families open their concrete-block homes to travelers for reasons that have nothing to do with Instagram.

The chicken bus drops you at a dirt crossroads where Lake Atitlán shimmers below, three volcanoes cutting the horizon. A teenager in a huipil—the traditional woven blouse that identifies her village—meets you there. No sign, no welcoming banner, just a shy wave and the assumption you'll follow her down a steep path into a community most guidebooks mention only in passing.

This is how Maya homestays in Guatemala actually begin. Not with reservation confirmations or welcome drinks, but with a walk into someone's real life, in a place where tourism exists but hasn't yet consumed everything.

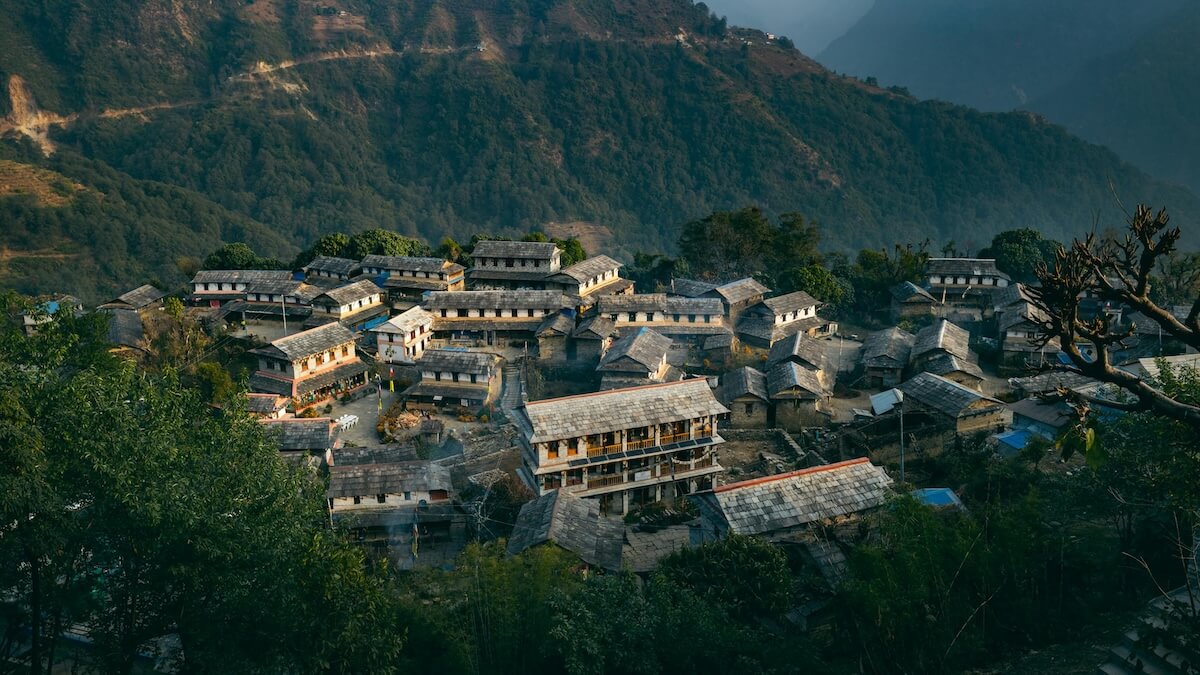

The Geography of This: Why Lake Atitlán

Guatemala's western highlands are home to over twenty distinct Maya ethnic groups, each with their own language, textile patterns, and cultural practices. The villages surrounding Lake Atitlán—places like San Jorge La Laguna, San Juan La Laguna, Santa Catarina Palopó—have maintained their indigenous identity more stubbornly than most.

These aren't museum pieces. They're working communities where people speak Kaqchikel or Tz'utujil as first languages, where women still weave using backstrap looms, where ceremonial life follows both Catholic and Maya calendars. The homestay programs emerged organically about 15-20 years ago as families realized that welcoming travelers could provide income without abandoning their way of life.

The setup is simple: families with extra space host travelers for a night or more, providing meals, a place to sleep, and—if you're willing—an honest look at how they actually live. No cultural performance, no sanitized presentation. Just daily life, with you in it.

What the Houses Look Like (And Don't)

First, let's dispense with any romantic notions: you're not staying in some Instagram-worthy traditional dwelling. Most homestay families live in concrete-block houses with corrugated metal roofs. Basic, functional, and emphatically not picturesque.

Your room will likely be spare—a bed or sleeping mat, maybe a small table, walls that might or might not be fully painted. Shared bathroom with cold water. No heating (nights at 7,000 feet get legitimately cold). Sometimes electricity, always intermittent. The aesthetic is 'functional poverty,' which sounds harsh but is simply accurate.

This is the point. You're not paying for comfort; you're paying—$15-20 per night including meals—for context. For the understanding that comes from sleeping where people actually sleep, eating what they actually eat, seeing how they actually manage with limited resources.

The contrast is jarring if you've come from Antigua or even from the more touristed villages along the lake. There are dogs everywhere. Chickens. Children. The sound of corn being ground for tortillas starts before dawn. Cooking smoke. Spanish mixed with Maya languages you won't understand. This is the reality that persists just minutes from the tourist zones.

The Family Dynamic: What You're Walking Into

Maya families in the highlands are multigenerational, tight-knit, and structured around work that never stops. Your hosts are likely to be a nuclear family—parents, children, maybe grandparents—all living in close quarters and all contributing to household survival.

The father probably works in agriculture, construction, or as a porter (Lake Atitlán has a robust tourist economy in the main towns). The mother manages everything domestic—cooking, children, weaving, maintaining the home. Children attend school when they can but also help with chores from a young age. This isn't child labor exploitation; it's economic necessity in communities where margins are impossibly thin.

Your arrival represents extra income—not wealth, but meaningful money that might cover school supplies, medicine, or unexpected expenses. The hosting isn't charity on their part; it's economic participation. They're professionals at hospitality, even if the setting is their own kitchen.

The family will be warm but not effusive. Maya culture values respect and proper behavior over demonstrative emotion. They'll welcome you, feed you generously, answer questions, but don't expect the over-the-top hospitality of some cultures. The warmth is there—it just expresses differently.

Language is the immediate barrier. Most families speak Spanish as a second language, and their Spanish is often basic. If you don't speak Spanish, communication happens through gestures, smiles, and the universal language of shared activity. Some families have teenagers with decent Spanish or even basic English. Others don't. Translation apps help. Patience helps more.

The Daily Rhythm: What Actually Fills the Hours

You arrive in late afternoon. Your host shows you to your room, points out the bathroom, explains meal times. Then there's an awkward period where you're not sure what to do. My advice: offer to help.

Evening preparation centers on food. Tortillas are made fresh for every meal—corn soaked in lime, ground by hand or with a mill, patted into perfect circles, cooked on a comal. If you ask, they'll teach you. You'll be terrible at it. They'll laugh, gently, and show you again. This is the cultural exchange that matters—not performative, just practical.

Dinner is typically black beans, rice, tortillas, maybe eggs or a small amount of chicken. Vegetables if available. Food is simple, starchy, and meant to sustain people doing physical labor. Portions are generous. Refusing food is genuinely insulting, so even if you're full, take something.

After dinner, if you're lucky, conversation happens. The father might ask about your country, your work, your family. The mother might show you her weaving—intricate designs that carry symbolic meaning she'll try to explain through limited Spanish and elaborate gestures. Children will be curious but cautious, watching you with the mixture of interest and shyness universal to kids everywhere.

You might visit neighbors, see the village school, walk to a viewpoint overlooking the lake. Or you might just sit in the kitchen, watching the family's evening routine unfold around you. Television if there is one. Homework. Animals being secured for the night. The ordinary stuff that constitutes most of life.

Morning starts early. Roosters ensure this. By 6 AM, the household is awake and moving. You'll be offered coffee (instant, sweet, milky) and breakfast (usually refried beans, eggs, tortillas). Then the family disperses to their various obligations—school, work, chores. If you're staying multiple nights, you might accompany someone—help with planting, watch weaving, visit the local market.

The Weaving: Why It Matters More Than You Think

Maya textile work isn't hobby crafting—it's cultural transmission. Each huipil (women's blouse) identifies the wearer's village through specific patterns, colors, and techniques passed through generations of women. The symbolism is complex: geometric patterns represent cosmology, animal figures carry spiritual significance, color combinations indicate status or occasion.

Your host mother almost certainly weaves. The backstrap loom—a deceptively simple tool where one end attaches to a post and the other to the weaver's back—requires skill built over decades. Women learn as children, achieve competency as teenagers, master complexity as adults. A single huipil can take months to complete.

If she offers to show you, pay attention. This isn't entertainment for tourists; it's her offering access to knowledge that defines her cultural identity. Ask questions. Try if she lets you. Buy something if you can afford it—the money matters, yes, but the affirmation that her work has value beyond the village matters more.

The textiles you see in Antigua's tourist markets? Many come from these villages, sold through middlemen who take the profit margin. Buying directly from the weaver ensures she gets full value for months of work. It's not charity—it's fair commerce.

Practical Arrangements: How to Actually Make This Happen

Most homestays are arranged through local organizations or language schools rather than directly. In Antigua, Spanish schools like San Blas offer homestay packages combined with language instruction—$140-170 per week including room, meals, and classes. This is the easiest route for travelers who want some structure.

For homestays without the language component, contact community tourism organizations directly. San Jorge La Laguna has an established program; San Juan La Laguna has cooperative associations that arrange stays. Email ahead, don't just show up. These are small operations without infrastructure for walk-ins.

Costs typically run $15-20 per night including three meals. Some families charge slightly more for private bathrooms (still cold water) or accommodations closer to 'tourist standard.' Pay in cash, in quetzales, and consider tipping if you feel the family went beyond basic hospitality.

Getting there: From Antigua, take a bus to Panajachel (2-3 hours, $3-4), then a chicken bus or boat to your village. Chicken buses are crowded, chaotic, and brilliant. They're also the primary transport for locals, so riding one is participatory rather than observational tourism.

What to Bring, What to Know, What to Avoid

Bring practical gifts: Coffee, sugar, rice, cooking oil, school supplies for children, or toiletries. Not tourist trinkets—things they'll use. Ask your coordination contact what would be most appreciated.

Dress conservatively: Highland Guatemala is socially conservative. Women should avoid shorts or revealing clothing; men should wear long pants. You're not in Antigua anymore—local standards apply.

Ask before photographing: Always. Especially with children. Some families are fine with photos; others consider it intrusive. Respect their boundaries.

Learn basic Spanish: Even minimal Spanish—greetings, food vocabulary, polite phrases—makes an enormous difference. Download a translation app with offline capability. Better yet, take a week of classes in Antigua first.

Avoid treating this as poverty tourism: You're not there to marvel at how people survive with less. You're there to understand a different system of values, a different relationship to community and land, a different definition of wealth that doesn't center on material accumulation.

Don't offer money beyond the arranged fee: If you want to contribute more, buy handicrafts directly, or ask the coordinator about supporting specific needs (school fees, medical costs). Random cash handouts create uncomfortable dynamics and set bad precedents.

The Awkward Truth: Tourism and Indigenous Communities

Guatemala's Maya communities exist in a complicated space. They're showcased as the country's cultural heritage while simultaneously marginalized economically and politically. Tourism provides income but also brings the risk of cultural commodification—turning living traditions into performances for outsiders.

Homestay programs navigate this tension by keeping control local. Families decide whether to participate, set their own boundaries, engage on their terms. The money stays in the community rather than being extracted by external operators. It's not perfect—no tourist encounter is—but it's structured to be as reciprocal as possible.

Your presence is ambiguous. You're providing income that helps families maintain their traditional lifestyle rather than migrating to cities. But you're also an outsider whose curiosity about their life stems from privilege. This tension doesn't resolve. The best you can do is acknowledge it and behave with humility.

The Guatemala you'll see in these villages isn't the Guatemala of resort zones or expat enclaves. It's a country where indigenous identity persists despite centuries of marginalization, where Mayan languages are still first languages, where women's textile work transmits cultural knowledge that predates European contact.

What You Take Away (If You Do It Right)

A night with a Maya family isn't transformative in the dramatic sense. You won't 'find yourself' or gain mystical insights. But you will understand, viscerally, how differently life can be organized. How community matters more than privacy. How wealth gets measured in relationships rather than possessions. How people maintain cultural identity while navigating modernity's demands.

You'll remember specific moments: the patient way your host mother showed you tortilla-making for the third time. The shy pride of the daughter showing you her school uniform. The father explaining, through gestures and broken Spanish, how the lake's water level affects everything. The grandmother who didn't speak at all but whose presence anchored the household.

You'll also remember your discomfort—the cold shower, the hard bed, the long silences when you ran out of Spanish vocabulary, the guilt of having so much when they have so little. That discomfort is part of the value. It forces you to reckon with your assumptions about what constitutes a 'good' life.

Most significantly, you'll understand that indigenous communities aren't anthropological artifacts or tourist attractions. They're living cultures adapting to contemporary pressures while maintaining connections to centuries of tradition. Your homestay family isn't frozen in time—they're navigating the same global forces as everyone else, just with different tools and priorities.

The morning you leave, your host mother will probably pack you food for the journey—tortillas wrapped in cloth, maybe some fruit. It's a gesture of hospitality that transcends the transaction. You pay her the agreed amount. She thanks you. You thank her. The exchange is awkward because you both know the gulf between your lives, and also insufficient because one night can't bridge it.

But you walk back up that steep path with something shifted. Not solved, not resolved, but shifted. You saw how people live when community is the organizing principle. When material simplicity doesn't preclude rich cultural life. When maintaining tradition in the face of modernization's pressure requires daily, deliberate choices.

That's what Guatemala's highland homestays offer: not comfort, not adventure, but context. The chance to understand that there are many ways to be human, to build family, to define value. And the recognition that your way—with its conveniences and comforts—isn't necessarily better, just different. That recognition, if you let it, stays with you long after the tortillas run out.

Comments

How did this story make you feel?

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!